Where are we going and why am I in this handcart?

True story: I was kidnapped in Russia in the late 90s. I managed to get out of the car, hide in a snow-filled ditch, then run to freedom. I was lucky not to get shot (by someone completely different, because Russia in the late 90s) on the way out of the dockside they’d driven me to in the middle of the night. And instead of ending up robbed and dumped in the cold silent waters of the Gulf of Finland, I made it home.

I say that to say this: I slept just fine that night, and the next, and in general since then. I’m not easily panicked or persuaded. But recently I’ve been disturbed during dreams and distracted by day by the very same question I had in the back seat of that car: “Where the hell are we going?”

I started writing because I wanted to warn my friends and family that the stock market crash of March 2020 (although scary at the time) was not the real problem. The real problem, I thought, was the extreme fragility of the modern financial system. But as I looked deeper into it, the story of money illuminated more about society, psychology, and history than I could have imagined.

Where money rests or flows, accumulates or drains away, constrains our actions as nations and as individuals. We can afford something, or not. This is obvious.

But what money is, how we conceive of and agree on it, forms an unseen frame on our thoughts. It shapes our life choices, habits, health, and sense of security. It determines politics, peace, pollution, and inequality. And almost no-one is talking about it.

I came to understand that the real problem is much bigger than merely the abrupt end of one financial system that the world happens to use right now. The real question is whether we as a society will, for the first time ever, understand why all the systems we tried so far were flawed, and whether we will consciously choose a different way – to finally claim that as-yet undiscovered human right: the freedom of money.

That’s why this ended up growing into an eight-part series. Every single concept in the first articles is relevant to the payoff in parts 6 and 8, I promise.

- A Brief History of Money

- A Brief History of Commercial Banks

- A Brief History of Central Banks

- A Brief History of Investment Banks

- The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 (coming soon)

- The Greater Depression of 2024 (coming soon)

- A Brief History of Global Financial Resets (coming soon)

- The Global Financial Reset of 2025 (coming soon)

Disclaimer

I’m not an economist or financial advisor, and this isn’t advice. It’s my inexpert opinion, full of conscious bias and dodgy jokes. So why bother reading it? Because I think with big topics like money and health, we’ve become lazy and entrusted our wellbeing unquestioningly to experts – which would be fine if the experts all agreed and the results were wonderful. But they don’t, and they’re not. At all. Much of what I’m saying (really only summarising from people smarter and better-informed) will be obvious, I think, in hindsight. But by then it’ll be a bit late.

Charles Kettering, holder of 186 patents, is famously supposed to have said, “A problem well stated is a problem half-solved,” which I thought would be a nice quote to summarise the goal for this series.

But the actual quote is a little darker, and much more appropriate:

A problem thoroughly understood is always fairly simple. Found your opinions on facts, not prejudices. We know too many things that are not true.

As quoted in Dynamic Work Simplification (1971) by W. Clements Zinck, p. 122 (emphasis mine)

What even is money?

Before there was money, there was only ̶Z̶u̶u̶l̶ stuff. A barter economy sucks because if I have a loaf of bread but you want a chicken, we can’t trade (the problem of double coincidence of wants), and everyone makes a sad face. It’s horribly inefficient because if I have a cow, but I only want some eggs, I have to either buy more eggs than Paul Newman can eat or carve up my cow (so long, Daisy) in order to make the trade.

So to be any good as a medium of exchange to facilitate our trade, money must be (unlike your chicken) accepted by most people, and (unlike my cow), easily divisible.

Cows really were used as primitive money though, along with other livestock. Why? Because they last for quite a while (longer than bread, and some celebrity marriages), can be transferred from person to person (catch!), and they’re both intrinsically valuable and hard to make. So while not excelling as a medium of exchange, they can function as a crude store of value. As my grandaddy never said, a cow today is about as useful as a cow tomorrow.

Lastly, if they’re all full-grown and healthy, one cow is more or less as good as the next. This means they can be a unit of account. For example, one wife is worth ten cows. Or whatever. Calm down dear I don’t mean you. You’re worth at least twenty.

The five properties of money

So in the end, good old Daisy tells us precisely what money is.

It’s a :

- Medium of exchange

- Unit of account

- Store of value

And exactly what its properties are:

- Divisible: Can be divided into smaller, useful-sized bits.

- Fungible: One bit is as good as another.

- Portable & durable across space and time: Can move it or keep it.

- Acceptable: The more people recognise it as money, the better.

- Intrinsically Valuable/Stable/Limited in supply: Most important.

It’s these last two properties – acceptability/adoption, and supply/value – that are critical to understanding which money will win the coming war.

Wait – what do you mean, which money?

Monies are always at war

The idea that there is only one form of money is a modern lie. There are many forms of money in some degree of use at any one time, and they are always competing against each other, just as nations, genes, and ideas do.

I don’t just mean US dollars versus Japanese Yen, although foreign exchange is a great example of modern magic money – the total amount traded in the forex market is about $2,409 trillion/year, about 27 times more than the value of everything useful made everywhere (world GDP ~$90 trillion/year). How is this even possible? We’ll find out in the next part, A Brief History of Banks.

What I mean is that, at any one time, there are many things people could – and do – use as money, alongside each other at the same time. Which one “wins” the fight for adoption depends, all other things being equal, on the perception of its value/stability/supply.

Coins replaced cows, shells, glass beads, and stone monoliths as money because people came to recognise their superior durability, portability, and stability.

It’s not just a historical thing. This kind of switch from one money to another could happen here and now, given the right circumstances. For example, when a country experiences terrible inflation, the people rush overnight to dump their own currency and buy foreign currency like dollars, even when that’s illegal. That’s pretty much what I think will happen soon, but everywhere at once, as we’ll see in the last part, The Global Financial Reset of 2022.

Gold is money

When people come, one by one, to prefer one commodity over another as a medium of exchange or store of value, this is natural money. After a certain tipping point, the network effect takes over and everyone has to do the new thing because everyone else is doing the new thing. This constant evolution results in a survival of the fittest.

As soon as a society is advanced enough to mine and mint gold, it bare-knuckles its way through all competition to become money. It’s incredibly important (for reasons that will gradually become clear) to appreciate that this happens always and everywhere as a result of the cumulative effect of individual choices, given sufficient freedom and time.

The fascinating thing is that nobody knew why gold was money until about 100 years ago. Everyone just did it. It was an emergent property of the market.

Daniel Oliver, Founder, Myrmikan Capital

Different people and societies disagree on what gods to worship, how many wives or husbands one can have, what counts as food and what day of the week it can be eaten, but they all freely choose gold as the ultimate store of value.

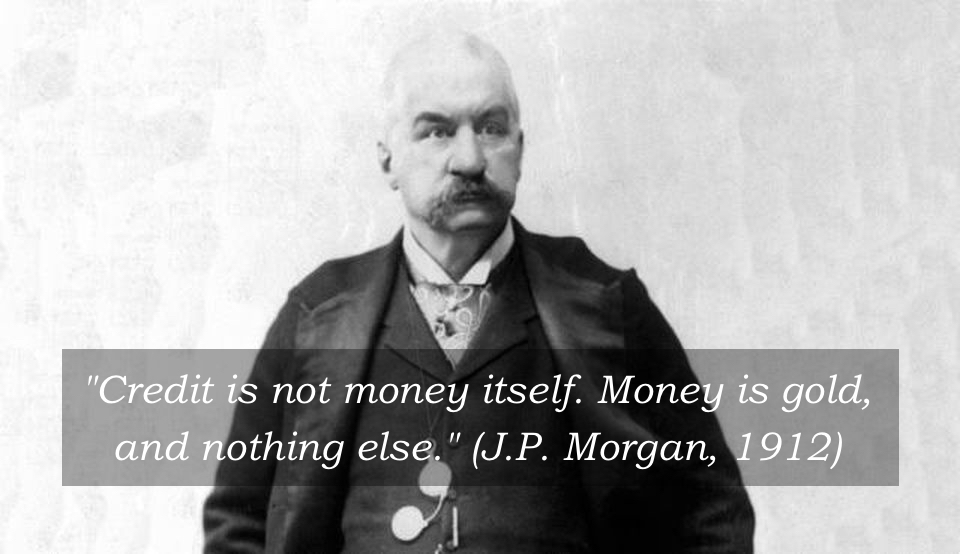

JP Morgan (more from him later) was the most influential banker in the world. He knew what he was talking about, and the layers of meaning to this quote are revealed as we go through the series.

Also, silver is money

Silver is the Robin to gold’s Batman, and their relationship tells us something more about money as a system. Gold is far more difficult to mine than silver, so the same size or weight of gold is far more valuable than the equivalent in silver.

Gold is less convenient to spend, especially on small things, so it’s naturally better as a store of value, while the more convenient silver is a better medium of exchange (copper, being far easier to mine, was only used for small coinage where inflation of supply wouldn’t have much impact). By knowing, or fixing, the relationship between the price of gold and silver, you can use them as units of account. Between them, they cover all three functions of money, which is why they’re always used together.

Fiat currency: because I said so

The opposite of natural money is fiat currency. This kind of money is never introduced fully-formed, or people would instinctively reject it. It is so weak that it does not long survive honest competition with natural money. It is the debased and the debaser, first of value, then character, and finally social order.

The Motley Fool, a well-respected investment website, defines it like this:

A fiat currency’s value is underpinned by the strength of the government that issues it, not its worth in gold or silver.

Incidentally, they, along with pretty much all mainstream experts, prefer the fiat system and think a gold standard would be a terrible idea (we’ll look at the gold standard in A Brief History of Global Financial Resets).

So how does fiat currency appear? First a society comes to prize natural money, gold and silver coins, for their inherent properties. Then the government realizes it can control this elemental force for its own benefit. It stamps the coins with the ruler’s face and decrees that only these kinds of coins are allowed to be used as money. The State establishes a monopoly on currency and backs it up with force.

fiat: an authoritative or arbitrary order / a command of will that creates something without further effort

Merriam Webster

At first, moving over doesn’t look like a big change. But as ever, it’s the principle that’s important. The freedom to choose one’s money is gone (and like all freedoms, not easily recovered). And money is no longer defined by its own intrinsic properties, but by an arbitrary standard – defined by those with power and imposed on those without.

Philosophically, coercion (the modus operandi of the State) is now inseparable from money. Practically, hard money will become easy money. It’s only a matter of time.

Hard money and easy money, part I

Gold is the most valuable money precisely because it’s hardest to create. It’s harder to mine enough gold for a coin than it is to raise a cow, carve a monolith, or create any other alternative. Although the element itself is relatively soft, gold is hard money.

In the beginning, currency must be equivalent to money – gold and silver. Either it’s literally made of precious metals, or it can be redeemed for them at any time (a gold standard). Otherwise, no-one would willingly accept it.

But once the definition of money is under the control of the State, they can change that definition with more “arbitrary orders”. These orders creep further away from equivalence with real money.

The most crude way to do this is simply to reduce the amount of actual gold in gold coins, and silver in silver coins. Then they can make more coins. They get more money, you see. Get richer just like that. It’s magic.

Fiat currency is the debased and the debaser, first of value…

Me, like 5 minutes ago

How does fiat currency destroy value? The debased coins simply aren’t worth as much. But hold on – the new ones by definition have the same nominal value as the old ones (it’s written right there), so what can this mean? Well, the real economy – cows and cars and crisps – hasn’t increased, but the currency supply has. So logically, each unit of currency can now purchase a smaller share of the whole pie. It’s worth less than it was. This is inflation, normally a boring statistic irrelevant to our daily lives, but about to become the defining aspect of our times.

Inflation is an increase in the currency supply.

Monetary inflation is an increase in currency units. Price inflation is an increase in prices. How you believe these two are connected defines what kind of an economist – and soon, how broke – you are. We’ll get into inflation in A Brief History of Central Banks. For now, the thing to remember is that while prices of individual things can move up and down for many reasons, monetary inflation eventually causes all prices to inflate. Austrian Economics > Modern Monetary Theory. There. I said it.

Because gold is the hardest commodity we have, new supply is low and predictable. With experience, people subconsciously understand this, which is the real reason we prize gold – not because it’s shiny. Monetary inflation on a gold standard is roughly between zero and 2% a year. Among other benefits, this places a strong constraint on State shenanigans.

Rome wasn’t burned in a day

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

George Santayana, The Life of Reason

The democratic Greek city-state of Athens was one of the first civilisations to standardise precious metals into coins of equal size and weight, i.e. proper money. Athenian money was high quality and widely accepted for trading in the Mediterranean. Their society (not coincidentally) prospered on this gold standard, producing so many artists and philosophers that Athens is referred to as “the cradle of Western civilisation”. Then they got into a long and expensive war with the Spartans.

Eventually, coffers depleted, they took to melting down their coins and replacing them with debased plated versions. This funded the war (hooray!). But prices rose (boo!), and soon after, they lost the war and were almost completely subjugated (oops).

Maybe prices rose because the supply lines were blocked. Maybe they were going to lose anyway. Maybe there’s no connection with coinage. Correlation doesn’t imply causation, after all.

But Athens then went back onto a silver standard as soon as they could. Why would any government willingly give up the ability to create currency on demand? They must have recognised the advantages of sound money. For now, let’s look for more examples. On to the Romans!

Turns out the Romans were good at orgies and aqueducts but not so good at learning the lessons of previous civilisations. Over centuries, the rulers of the Roman Empire, to pay for warfare and welfare, debased the original gold and silver coins – and they got really creative.

They invented shrinkflation, by reissuing the same coins but smaller. They mixed lesser metals into the coins. And they clipped little bits off the edge of your coin when you entered a government building, then melted them down to make new coins. Talk about adding insult to injury – directly taxing you to fund inflation that then makes you poorer!

By 301 AD, there was almost no gold or silver left in the coinage, price inflation was rampant, and Emperor Diocletian tried to impose both price and wage controls – the last resorts of rulers that don’t understand economics. Of course, they didn’t work.

In Diocletian’s time, in the year 301, he fixed the price at 50,000 denarii for one pound of gold … In 337, the year of Constantine’s death, a pound of gold bought 20,000,000 denarii.

Professor Joseph Peden “Inflation and the Fall of the Roman Empire”

Debasing the Roman currency directly caused hyperinflation of 40,000% in a single generation. This made efficient, far-sighted trade and taxation impossible, and contributed to the fall of the Roman Empire (there were many reasons, but you absolutely cannot finance an empire on money that people no longer trust).

We could look at the problems paper money had when it was invented by China in the Tang dynasty, or other instances, as in this Top Five list by Investopedia, which includes some concise causes of hyperinflation: “Distrust or disfavor with the ruling government. Wars and panics. Massive printing of money with nothing to back or support it.” Does that sound familiar today?

Anyway, you get the point: “Fiat currency is the debaser, first of value … and finally social order.”

The currency cycle in history

Creating fiat currency doesn’t always end in hyperinflation. But it always ends in trouble. Don’t believe me? Try and find a fully fiat currency – one that is not redeemable into gold or silver – that’s functioned as reliable money for more than a century (i.e. has not failed within “living memory”). Go ahead, I’ll wait.

“Paper money systems have always wound up with collapse and economic chaos.”

Howard Buffett (Warren Buffet’s father), 1948

Today, for the first time in history, every currency in the world is a fully fiat currency (unbacked by precious metals) all at the same time. Bear that in mind as we explore the system – it is an unprecedented experiment.

By contrast, not only has gold been money for over a thousand years, it’s the money that we always return to when other monies fail.

Here’s a simplified summary of the currency cycle up to the modern age:

- In a free market for money, the people choose sound, natural monies.

- The State removes that freedom and mandates a fiat (paper) system backed by a gold/silver standard.

- The government wants to spend more than it earns (deficit spending, usually on warfare & welfare), and abuses its power by over-printing or debasing currency to pay for it, bending or breaking the hard money standard. Because they can.

- Confidence in the currency goes down and inflation goes up. If the government still wants to spend more than it earns (who doesn’t?), they print or debase more currency and the cycle intensifies.

- Eventually, there is a financial reset: a soft reset, where the currency goes back onto a gold or silver standard, or a hard reset, where the currency is destroyed, damaged, or devalued, along with the social order that relies on it.

This destruction of value can only be created by force, and only by a government that is out of control – because the people don’t see the danger or don’t have the option left to change anything.

Of dead horses and kittens

In case you think I’m being extreme or somehow fringe in saying that money is gold, I’ll give the last word (and I could fill a whole article with quotes like this) to Alan Greenspan, who for twenty years ran the Federal Reserve, the largest fiat money-printing central bank in the world:

I view gold as the primary global currency. No one refuses gold as payment. Credit instruments and fiat currency depend on the credit worthiness of a counterparty. Gold, along with silver, is one of the only currencies that has an intrinsic value. It has always been that way. No one questions its value [since it was] first coined in Asia Minor in 600 BC.

Dr Alan Greenspan, interview in Gold Investor, February 2017

Well, we made it to the end. Congratulations – you now have a more sound grasp of monetary history than many of our politicians. To celebrate, here’s a picture of a lovely kitten.

The concept of money we’ve examined here is useful – and, I believe, true – but becomes incomplete in the modern era. To really see where this handcart might be heading, we need first to tell another story, much stranger and more outrageous – the history of banks.

🌍 Share this: