Free money, anyone?

This is the third in a series of eight articles:

- A Brief History of Money

- A Brief History of Commercial Banks

- A Brief History of Central Banks

- A Brief History of Investment Banks

- The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 (coming soon)

- The Greater Depression of 2024 (coming soon)

- A Brief History of Global Financial Resets (coming soon)

- The Global Financial Reset of 2025 (coming soon)

In the previous article, we learned why all our money is now magic money, and how we’ve become addicted to interest on deposits. In this article we will see who is behind the biggest theft in history – of most of the value of all the money in the world.

Piggy in the middle

From the ashes of the Stockholms Banco arose the Swedish Riksbank in 1668, which claims to be the oldest central bank in the world. The Swedes used copper because they didn’t have enough physical silver and gold to make enough coins. As we saw in A Brief History of Money, copper isn’t a very hard money.

The Riksbank also lent the government money (which it needed to fund wars with Sweden’s neighbours) and acted as a middleman for trade.

A few years later, in 1694, the Bank of England was created. It’s one of the oldest surviving central banks, and the “model on which most central banks around the world are built“.

This bank, too, was created by armed conflict. England had just been crushed by France at sea, and no-one would lend them any more money. As a bribe to get people to lend it money, the broke government formed a group for rich creditors and gave them the awesome privilege of issuing bank notes, and a cool name: “The Governor and Company of the Bank of England”.

From this gangsta start, the Bank of England grew gradually into its role as central bank. It managed the national debt. It also functioned as a clearing house for other banks: it helped move money from one bank to another to reduce counterparty risk – the risk that a trusted third party turns out not to be trustworthy after all.

To help create trust in the banking system, other banks had to keep a fixed fraction of their deposits as reserves at the Bank of England. And the Bank acted as lender of last resort for the first time in the panic of 1866.

The central banks of Sweden and England acted (sort of) responsibly, and have lasted until the present day. In France, however, things were much more exciting.

Hard money and easy money, Part II

The story of the Banque Royale, the first central bank of France, is relevant to us because it’s a template for how excessive money-printing and speculation turn out.

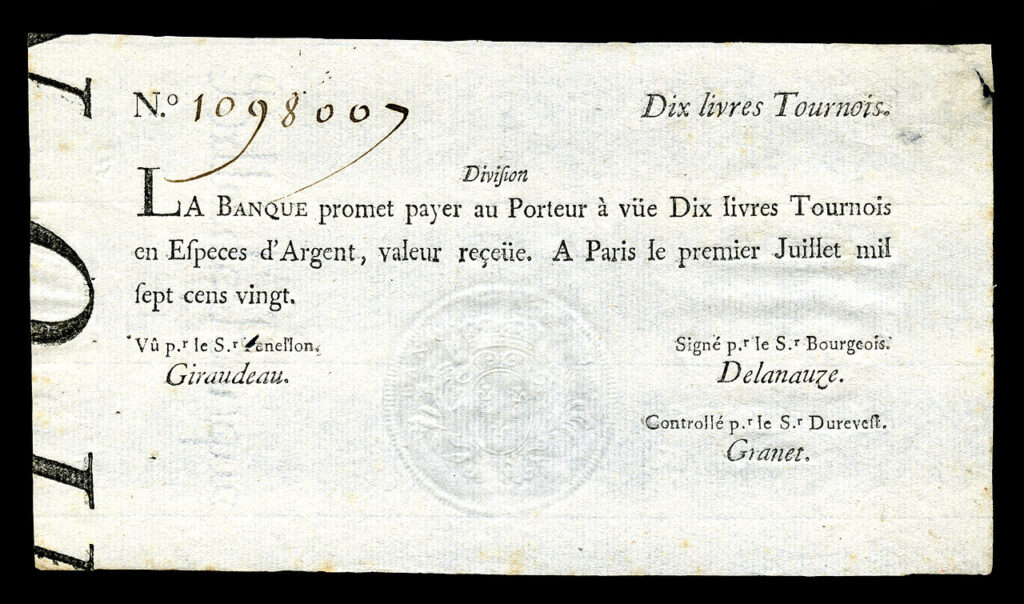

The Banque Royale of France was founded in 1716. It printed paper currency, allegedly backed by a gold standard, to bring France out of the unpayable debt created by the Sun King Louis XIV – and it worked. A bit too well.

The looms of the country worked with unusual activity to supply rich laces, silks, broadcloth, and velvets, which being paid for in abundant paper, increased in price fourfold. … New houses were built in every direction, and an illusory prosperity shone over the land, and so dazzled the eyes of the whole nation, that none could see the dark cloud on the horizon announcing the storm that was too rapidly approaching.

Charles Mackay, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

The bank immediately printed too much currency. The boom and bust cycle happened on fast-forward because the Minister of Finance, the gambler and convicted duellist John Law, used the state’s finances to prop up the stocks of his own enormous private company, the Mississipi Company, such that they were basically inseparable. John Law believed, like most modern economists do, that money is just credit/debt, and so logically there were no constraints on its creation. The state bank’s currency bubble was compounded by the company’s stock bubble, and they inflated and burst together.

Inevitably, price inflation followed currency inflation. Then came a flight into hard assets, as people quickly exchanged their untrusted notes for gold and useful things they could hold, ending in a full-on bank run. Just four years after it started, the bank broke its promise to exchange currency back into gold, private transactions in gold or silver were made illegal, and the currency was devalued. John Law was exiled, and France, dragging Europe with it, went into a depression for decades. She did not experiment with paper money again for almost a century.

(Image courtesy of National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution)

I predict that everything that happened to the French three centuries ago is happening or will happen to us now (as we’ll see in The Greater Depression of 2021 and The Global Financial Reset of 2022).

Collateral Damage, Part I

If Charlie the Carpenter takes a loan to buy a house, he can use the house as collateral for the loan. If he can’t pay back the mortgage (Charlie, sort your life out), the bank can take the house instead of the money. The debt is secured by the house, or something else of value that Charlie owns. It’s a secured or collateralised loan.

Collateral is something real and secure – a hard asset – that makes something unreal and insecure – a debt – more real and more safe.

The saga of how the money system lost its mind is in large part the changing definition of what is accepted as collateral.

In the beginning, the reserves of gold in a bank’s vaults were a bit like their collateral, in that they acted as security underpinning the loans that it created. As we saw in A Brief History of Commercial Banks, the further that magic money gets from this real basis, the more risk there is. But this is just the beginning.

John Law accepted French government debt (bonds) as payment for shares in his Mississippi Company. Instead of shares being purchased with gold, and gold being lent to the government, both sides of the equation became paper promises. The shares promised future earnings from the Company. The bonds promised future payment of interest and the return of the principal (the original loan amount) in paper money – which was itself a debt, being a promise to swap notes for gold.

As the unreal layers increased, so did the ways it could unravel, as it quickly did. The point is: the less real the collateral, the more risk there is.

Central banks good, two legs bad

We’ve seen that successful central banks started off doing these things:

- Lending the government money

- Issuing paper money (backed by gold) to make the financial system work more smoothly than physical silver and gold coins could

- Preventing counterfeiting

- Ensuring that the value of money doesn’t collapse

- Being a trusted third party for financial transactions

- Being the Lender of Last Resort

When they stick to doing only the things in this list, we can call central banks passive. Early, passive, central banks were necessary and useful.

In modern times, though, all central banks are active in trying to control the economy. They’ve drifted from being guardians to being central planners.

Every modern central bank is different (go down that rabbit hole if you wish), but they all do similar things. Let’s revisit our two oldest central banks. In addition to the obvious stuff like regulating other banks and producing notes, the Riksbank’s website says that their policy:

..is aimed at attaining the inflation target [2%], and at the same time it is to support the objectives of general economic policy with a view to achieving sustainable growth and high employment.

The Bank of England says that their job is to: “keep inflation at 2%, because low and stable inflation is good for the UK economy. We do this by setting the core interest rate at which we lend to the banks, and by buying (or selling) assets.”

For a couple of centuries, the freedom-loving ‘Muricans had rejected a central bank each time it was introduced.

We had no central bank from 1836 to 1913. That was one of the greatest periods of prosperity in world history. The invention of the telephone, the reaper, the airplane, radio, phonograph, electricity, massive increases in productivity, and great industrial successes. America grew like crazy with no Central Bank.

James Rickards, former CIA financial analyst and advisor to the Pentagon

But it was not to last. Although the US had a gold standard in name, they also had a rampant fractional reserve banking system. Its rules were more relaxed than in Europe. The State required banks to keep only a very small fraction of their customers’ money as reserves, so they were especially vulnerable to bank runs.

Banks allowed companies to use stocks as collateral to borrow large amounts of money. Stocks, of course, are themselves paper promises. Because their collateral was not really real, the companies ended up too highly leveraged – they had too little hard money backing too much debt. If the value of their stock collateral were to drop, the companies would owe more to the banks than they could pay back.

Inevitably, this unstable system, triggered by some random events, created a massive series of bank runs and bankruptcies that erupted in 1907. J.P. Morgan had to personally organise a rescue from major bankers (resorting to locking them in his library until an agreement was reached), and something had to change.

The US could have changed the rules to fix the root causes: too much leverage, unreal collateral for lending, and fractional reserve banking. But this would have gone against the profits of the financial class, and so the political class instead created One Bank to Rule Them All.

In 1913 the Federal Reserve system was established under President Woodrow Wilson. Under the Federal Reserve Act, the Fed’s goals are: maximising employment, stabilising prices, and moderating long-term interest rates. The Fed was an active central bank right from the start.

So in addition to what passive central banks did, modern, active, central banks also try to maximise growth, employment and stability. And how well are they doing?

The short answer: Giving a bank a printing press and asking it to manage the economy is like giving petrol to a pyromaniac and asking him to look after the barbecue.

The Central Scrutinizer

Here’s a funny thing: because money is how we pay for commodities (stuff), we forget that money itself is a commodity that is bought and sold in a market, and its price is interest.

And just like any other market, the money market can be run with smart rules or stupid ones, transparently or crookedly, as a free market, or centrally planned.

Incredibly, while the free world has rejected central planning of our commodity markets, it has, by accepting active central banking, submitted to central planning of the most important market of all.

The Central Bank has a lot to handle and it is best not to interfere with its competence.

Vladimir Putin

Complex systems balance themselves

The financial economy is an extremely complex system. Complex systems must balance themselves with the right feedback loops – or become unstable and risk collapse.

Interest rates are one example of a negative feedback loop (a home thermostat is the classic example). Low interest rates make borrowing money cheaper. People start to save less and borrow more. When people are borrowing too much, the risk that people won’t be able to repay the loans increases. Interest rates must go up to compensate. Credit becomes more expensive and saving pays more. So borrowing slows down or reverses, people get more of a buffer in savings, and the risk in the system goes down again. And then the cycle reverses. Ideally this happens in a narrow, stable range rather than having big swings, but that’s another story for another time.

It balances itself. Just like no-one needs to “manage” the bread supply to London: price signals for bread and a free market take care of that.

If interest rates are set freely and responsibly, they are honest price signals and negative feedback loops for money.

A shitty situation

What happens if you interfere with feedback loops so they don’t work properly? The recent run on toilet paper in the West was triggered by the external factor of coronavirus lockdowns, and was therefore short-lived, as demand normalised and producers were free to supply as much as they could of their own accord. It’s not socially acceptable to raise prices of things people need in an emergency, but in normal circumstances, price changes act as honest signals, micro-adjustments to increase, decrease or change production and consumption.

But truly committed socialist or fascist (both command-and-control) countries deprive themselves of these feedback loops, favouring ideology over reality, and therefore shortages are a way of life, including basic stuff like books and pens, food and medicine, and yes, even toilet paper.

Although terminal cases of socialism make easy targets, I’m not arguing for the Left or Right. Beyond both, and more important, is the dimension of statism – how much power we give to governments of whatever colour, and in this story, especially the power to distort the markets.

One size fits all

When I lived in Russia, it was freezing indoors in September and boiling hot in April. Why? Because flats didn’t have their own heating controls. It was true central heating – hot water piped to everybody from the nearest big plant, and it had only two settings: ON FOR EVERYONE or OFF FOR EVERYONE. The Authorities, whoever they were, turned it on in the autumn and off in the spring, regardless of the actual temperature. I’m informed that they still haven’t managed to get rid of this system.

In the West, we might laugh at this, but we do the same thing in finance. Central banks set interest rates centrally. They set one rate at which they lend to other banks. This causes those banks to change their own lending rates. Lowering the base interest rate causes banks to lend more.

Low interest rates, more credit, and less saving have the same effect as printing money – they increase the money supply, regardless of the actual need for an increase or decrease. Occasionally central banks destroy money and raise interest rates, but their default is overwhelmingly mo’ money – no problems.

Central banks have gotten out of the central banking business and into the central planning business, meaning that they are devoted to raising up – if they can – economic growth and employment through the dubious means of suppressing interest rates and printing money. The nice thing about gold is that you can’t print it.

James Grant, founder of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer

Increasing the money supply is really the only tool the central bank has – and if they only have a hammer, everything starts to look like a nail.

What effect does hammering the economy have? It distorts honest price signals and discounts local feedback.

The map is not the territory

Why were there no Soviet-era celebrity chefs? Because during the imposition of planned economics on Eastern Europe, you never knew what would be in the shops, if anything. People would queue for hours or days in hopes of getting something.

Such shortages are not (just) incompetence. They’re caused by centralisation. The bigger the system, the more a central planner must rely on an abstract model.

If ruling by an abstract system eventually causes shortages, then under active central banking we should expect periodic shortages of money. We call these recessions – or even liquidity crises.

Also, the more centralised the abstract model is, the less it can take account of feedback signals in a local context. Farming, like any real-world enterprise, is a complex mess of local signals like the weather, soil quality, pests, supply and demand for different foods, and so on. Centrally planned farming is thus a contradiction in terms that in the 20th century killed more people than the Holocaust.

How does this apply to banks? In theory, every lender chooses the interest rate for each loan based on general risk (how the economy’s doing) and specific risk (how risky the borrower is). If lenders judge this risk correctly, their reputation improves and they get a greater share of business. If they get it really wrong, they go broke. Given a free hand – and with individual banks being allowed to fail – the banking system as a whole should get really good at it over time, and loans, and the system built on them, should get more secure.

Interest rates adjusted for each borrower are local feedback signals. If Charlie goes to Bob’s Bank but can only get a loan at 40% interest, which is an accurate measure of his risk, he might decide it’s not worth borrowing. He might even plan to pay back other credit and try to save.

But now imagine Bob’s bank is influenced by a central policy to suppress interest rates, and they give him a loan at 20%. Crazy Charlie gets a dishonestly lower absolute interest rate just because a central planner, who doesn’t know him, says so. Even if it’s higher, relatively, than Alice, who got 10% because she’s financially sensible, it’s clear that some unnecessary risk has been created. Charlie is free to fund some activity he probably shouldn’t.

When you manipulate interest rates, you change not only the value of money but also people’s time preferences. Artificially low rates make them more likely to consume, and much less likely to save. It discourages capital accumulation and punishes the prudent. It causes all kinds of distortions and misallocations of capital in society – people start doing things that they otherwise wouldn’t do.

Doug Casey, A Government-Ordered Depression

When I said, in the first article in this series: “Fiat currency is the debased, and the debaser, first of value, then character, and finally social order,” time preference is part of what I had in mind. More on that in The Global Financial Reset of 2022.

In this way, distortion of the market, distortion of people’s behaviour, stored-up instability, and too much money are the gifts of active central banking. And what of the inflation that they engineer for our own good – what is it, really?

Inflation is theft – by design

When the government/central bank creates, let’s say, a dollar, they immediately spend it themselves, or give it to the banks, with whom they enjoy a mutually enriching relationship.

The government or their friends get the full purchasing power of that dollar right away. But where did that power come from? It came from taking a little bit from all the other dollars in existence. They are weaker. They all lost some purchasing power today, and more tomorrow. When you spend your dollars in the future, they’re worth less than those that the government and the banks got. In this way, currency creation is a constant drain on the resources of the man in the street, an inescapable, invisible transfer of wealth from ordinary people to the political class.

This has been known for centuries, and is called the Cantillon Effect, after the economist Richard Cantillon. Because rich people own financial assets (whose value goes up as newly created money flows into them), and poor people rely on wages and cash savings (whose purchasing power goes down due to higher commodity prices), inflation makes the rich richer and the poor poorer.

Inflation is the true cause of rising wealth inequality.

Not capitalists or the patriarchy, not Jeff Bezos in particular or The White Man in general. The structure of the financial system. Soft money. It’s right there hiding in plain sight.

Remember, the government doesn’t have any wealth of its own. Anything it promises to one group it has first to take from productive people, right now via taxes or by robbing the future via the stealth taxes of debt and inflation.

Alan Greenspan, who went on, despite his early anti-establishment views, to become Chairman of the Federal Reserve, put it quite clearly:

“In the absence of the gold standard, there is no way to protect savings from confiscation through inflation. There is no safe store of value.”

Alan Greenspan, Gold & Economic Freedom, 1966

Niall Ferguson, who literally wrote the book on this topic, says:

Money is only worth what someone will give you for it. An increase in its supply will not make a society richer, although it may enrich the government that monopolises the production of money. Other things being equal, monetary expansion will merely make prices higher.

The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World, Penguin 2008

Or in other words, governments can print money – but they can’t print wealth.

Recall that the most fundamental function of money is a store of value, and the first duty of banks is to keep it safe.

Central banks are explicitly charged with price stability!

Inflation is the opposite of price stability. Let’s ask Paul Volcker, who was a very well-respected and accomplished central banker, who successfully fought to bring inflation back under control in the early 1980s, when many said that it was impossible (spoiler: he raised interest rates).

It is a sobering fact that the prominence of central banks in this century has coincided with a general tendency towards more inflation, not less. If the overriding objective is price stability, we did better with the nineteenth-century gold standard and passive central banks, with currency boards, or even with ‘free banking.’ The truly unique power of a central bank, after all, is the power to create money, and ultimately the power to create is the power to destroy.

Paul Volcker, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, quoted in his Lifetime Achievement Award

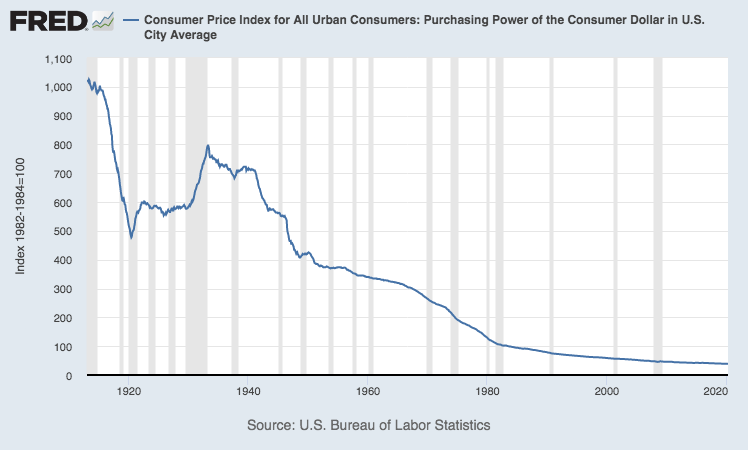

And what does a “general tendency towards more inflation” actually look like?

This shows the loss in purchasing power of one dollar, from 1913, when the Fed was created, until the present date. $1 then is now worth just under 4c, which is a loss of more than 96%. And that’s using official statistics.

Well done on “ensuring that money retains its value”, boys. Really, outstanding job.

How fast is money?

Inflation and deflation is just the movement of prices, e.g. of bread, milk, and so on, up (inflation) or down (deflation). Let’s get a little more precise about what makes them move.

Prices are velocity x currency supply

The velocity of money is the speed at which people spend their money. Although there’s a bit more to this simplified equation (and Austrian economics thinks velocity is a phantom), I reckon it’s a useful shortcut.

If people spend money as soon as they get it, that makes prices go up.

When people are quickly getting rid of money to gain, say, food, gold, cars, golden cars, or what-have-you, this is high demand, which is is soon matched by high prices. The reason why they’re buying more quickly doesn’t matter here. They could have lost faith that fiat currency will keep its purchasing power, they could be desperate because of some change in society, or they could have too-easy access to money through cheap credit.

On the other hand, if people are slowing the velocity of money by hoarding cash under their mattress for whatever reason, that means they’re not spending money on cosmetic surgery, poodles, cosmetic surgery for their poodles, or whatever else people do. Demand falls, and prices must fall too, until they become cheap enough to persuade people to become customers again. This simple idea helps us understand deflation.

Deflation: who’s afraid of the big bad wolf?

When central banks say they want to keep inflation low, they mean two things:

- They’re afraid of prices shooting up to match the inflated currency supply (unfortunately, the longer this distortion goes on, the worse it will be when it finally happens).

- They’re even more afraid of deflation.

So what’s wrong with deflation?

When bad things happen

Deflation in our magic money system is usually caused by bad things happening. When businesses slow down or close during recessions, that causes deflation. Bank runs – terrible crises of confidence in the financial system – are incredibly deflationary, because they destroy huge amounts of the imaginary money that was created by banks. If anything big and bad happens that makes people fearful, they spend more slowly, velocity of money goes down, and you also get deflation. This association with bad things is one reason why people are afraid of deflation.

When good things happen

Deflation also comes about as a result of things that are generally positive. People saving money instead of buying stuff they don’t need on credit takes money out of the system and so is deflationary. But when almost half of Americans have zero savings, making them tragically vulnerable to, say, State over-reaction to a pandemic that wipes out the job market, we can be brave and say people should save more. When people pay back their debts to banks, this is also very deflationary for currency, but it’s generally a good thing and makes us financially more resilient.

Regardless of whether the cause is positive or negative, price deflation in itself shouldn’t be something to fear.

Your money is worth more

If prices go down because of deflation, money’s purchasing power goes up. The average Joe feels better off. They can afford to save a bit more, or invest, or buy some of those cool LED lights that go under your car.

And if you think about it, prices should be going down. We’ve been busy inventing ways to do things more efficiently for a very long time, and that translates into lower cost.

Debt deflation

Deflation is not good, though, for people or businesses who are heavily in debt. If the prices of products, value of assets, and even wages fall, this is ok if they all fall more or less together. But if your debt stays at the same amount, you’re effectively getting much poorer. For example, if you take an 80% mortgage, and next year your house is suddenly worth 30% less, your debt is now greater than the worth of your house and you have negative equity.

Most of the time, deflation is unambiguously a positive trend for the economy, but…in an economy dominated by debt-fueled asset price bubbles, deflation can lead to a temporary financial crisis and period of liquidation of speculative investment known as debt deflation.

Investopedia

Investopedia’s short article about deflation illuminates many of the things we’re talking about, and it’s really worth reading the whole thing.

Deflationary spiral

The scary story the central banks tell us is that if we ever let deflation get hold, we’ll go into an unstoppable downward spiral. Now it’s true that deflation from our current centrally-juiced, unbalanced state will cause liquidations of badly invested money (e.g. bankruptcies of poorly run companies) that will last for some time. The central authorities won’t be able to stop it, once it gets going. It will be a painful shock as we move to a healthier state. But a shock is not a spiral.

The fear is that people would stop buying things today because their money would be worth even more next week. This drop in demand would cause a greater drop in prices, which would cause more deferred spending, and so on until, presumably, no-one buys anything and we all starve to death in our uncool cars.

This is just nonsense. Prices are part of a complex system. Left alone, they will balance themselves. As Mr Volcker says:

The idea that when people see prices falling they will stop buying those cheaper goods or cheaper food does not make much sense. And aiming for 2 percent inflation every year means that after a decade prices are more than 25 percent higher and the price level doubles every generation. That is not price stability, yet they call it price stability. I just do not understand central banks wanting a little inflation.

Paul Volcker, quoted in Recent Economic Data Shows the Good Side of Deflation

The real reason central banks “want a little inflation”

If deflation increases the purchasing power of the ordinary person and improves our standard of living, why are central banks so against it?

If keeping inflation positive and interest rates artificially low causes everyone to run up too much debt, why do central banks want it?

Because governments, banks, and big business have no intention of paying back their debt.

They can’t. For banks, debt is their business (money itself is now debt, remember). And governments and indebted businesses can’t afford it. When the day comes to repay their debt, they just borrow again instead. They desperately want interest rates to be lower than inflation, which means “real” interest rates are negative. They need inflation to grow their income (from taxes or business activity) faster than interest grows their debt so that they don’t drown in it.

Governments are so heavily indebted that they have a vested interest in somehow engineering negative real rates of interest.

The Spectator, April 2020

Do we need central banks?

We need some way of issuing money and preventing it being counterfeited. And some way of verifying the trustworthiness of financial transactions. The other functions of passive central banks, lending the government money and being a Lender of Last Resort, would not be important if we had a stable financial system and prudent government, but let’s include them and say passive central banking is ok.

Everything else that active central banks do, we do not need or want.

The surprising thing is not that central planning, inflation by default and constant low interest rates are bad for you, me, and society as a whole – it’s that we swallowed the idea that they’re normal, or even good for us.

When central banks distort the free market of money (which is now literally their job), they increase risk, cause too much borrowing, and create too much money. Now, where does this money – and risk – end up being concentrated? Step forward, investment banks.

🌍 Share this: